Reviews and Recollections - 1979 to 81 - The Factory closes

Lazy popular historians and ignorant politicians or journalists tend to portray the 1970s as the era when British industry was crippled by ‘the unions’ and a tidal wave of wildcat strikes. As if the entire UK was as shown in the comedy film, “I’m All Right, Jack!” However the reality was rather different for many of us who worked in small manufacturing firms. These made up a larger part of the economy than you might think from seeing TV documentaries about the 1970s, and their problems often were rather different!

As a working environment, Armstrong at the time was probably fairly typical. The people who worked there did so almost as a sort of extended family. The production line workers were taken out on a works outing each year, often to a London show or musical. And there were presents at Christmas. On one occasion when sales were low, some had to be laid off and they found jobs elsewhere. However when things picked up many of those affected quit their new jobs and came back! There was no union because the people didn’t particularly feel they needed one. The production line and test/service department was all in one room and everyone could see what everyone else was doing. They could also see if they were making many sets each day and they then went out, or if sets were being stacked up unsold. So knew if business was good or not. The real problems that led to Armstrong ending production had nothing to do with industrial unrest or unions...

The main problem arose because the factory at Warlters Rd was leased from the National Coal Board Pension Fund (NCBPF). As the lease approached its end, the NCBPF wanted to take back the factory site and building to sell/use it for redevelopment. They felt they could make a higher return if land was used for something else, not as a factory. They had some difficulty sorting out what to do, and as a result they actually allowed Armstrong to continue for a few years after the lease ended, rent free! But this was only until they had finalised their plans, and it was made plain that at that point the factory would go.

At this time, Armstrong was owned by the Smith brothers, Alan Farquharson, and Alex Grant. The Smiths weren’t really interested in Hi-Fi as such. Their involvement was primarily on the basis of being financial investors in small/medium scale businesses, looking for a reasonably profitable return. Armstrong were still making a decent operating profit. But the refusal of the NCBPF to agree a new lease meant a new factory would have to be set up somewhere else. That would entail providing sufficient capital for putting together a new production line, etc, along with new machinery.

For a business investor that clearly raised the question, “Would the return justify this new capital investment”? A decade or so earlier the answer might have been a clear “yes”. But in the 1970s the Japanese were having a very serious impact on the Hi-Fi market in the UK. So although more people than before were wanting to buy Hi-Fi, many new models at competitive prices, were appearing. The challenge here wasn’t simply that wide range and competitive prices, etc. The reality was that some of these competitors were very large international corporations.

For example, companies like Hitachi or Sony often developed their own transistors. And for a time they made the best audio and rf transistors, etc, specifically designed for Hi-Fi equipment. They tended to put their newest and best examples into their latest amplifier and tuners. But only sold them to other manufacturers after they’d released newer models using improved devices! Other companies like National Panasonic (‘Technics’) and Yamaha were vast corporations compared with a tiny ‘family’ private companies like Armstrong. They didn’t just make Hi-Fi, they made all kinds of things from surfboards and pianos to power stations and shipbuilding. Given all this it became quite clear that they could easily dominate the UK Hi-Fi market of the period. At the time we joked that the Japanese probably had more people carrying around their internal memos or sweeping offices than we had in total working at Armstrong!

So by the second half of the 1970s, it was understandable that the Smiths felt that it simply didn’t make financial sense for them to put up the capital for a new factory with the same capability as the one that was going to be demolished by the NCBPF. Instead it was decided that the Armstrong factory would be closed, and production ended. The company made a profit to the end, but lost the factory it needed to continue.

During this period I had been working on developing amplifiers for the planned next range Armstrong intended to eventually released to replace the Series 600 units. At one time the success of the 600 range did make us consider the possibility of what was briefly referred to as the ‘phoenix’ range. The idea was to use the existing dies, jigs, etc, and make new models that looked similar to the 600, but had re-designed and upgraded amplifier and tuner circuity. This would minimise the manufacturing start-up costs of building a new range. However it would at that time have imposed some serious limitations on what could be done. For example, one of the main limitations of trying to put a more powerful amplifier into the old 600 units was that the heatsinks at the back were simply too small to handle the higher powers. In the 21st century this wouldn’t now be a problem given the availability of ‘digital’ (switching) power amplifier which are able to deliver high powers whilst running cool. But in the late 1970s it was impractical. So the idea was abandoned.

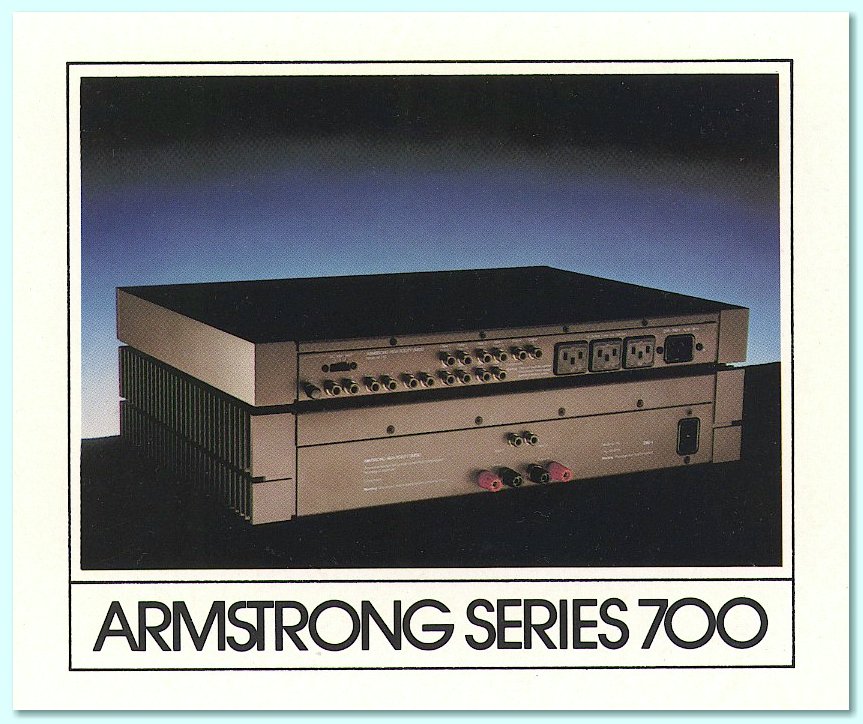

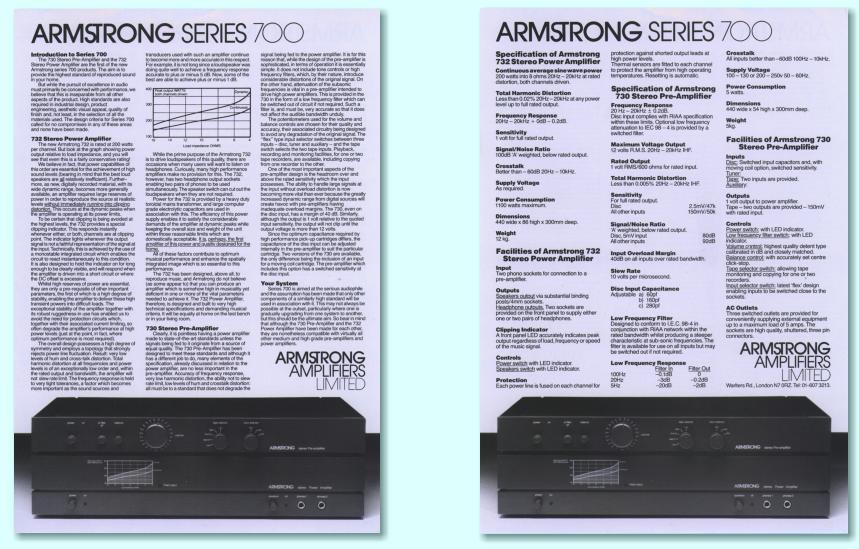

Instead the plan was to move up-market and develop what these days would be regarded as a ‘high end’ set of amplifiers and tuners. Since these were to have a high level of performance they would be expensive, and go for a smaller market share who would be willing to pay more for items made to a “no expense spared” standard in small quantities. Something more appropriate for a small production facility.

At the time the most powerful highly regarded amplifiers tended to deliver powers around 100 Watts or less. Because of the transistors available these often included ways to limit the current to protect the transistors. However there was tendency for loudspeakers to become less efficient and more current demanding “difficult” loads. So the pressure was on the devise an amplifier that was more powerful, and happy to drive large currents and voltages into such loudspeakers.

In addition, throughout the 1970s the talk of “digital audio” grew as various companies around the world were experimenting with digital audio recording and playback. It became plain that both pre-amplifiers and power amplifiers would need to be able to deliver a much higher dynamic range, with lower noise and distortion, for ‘line level’ inputs from the eventual digital audio players, etc, which promised to appear fairly soon. These were all factors that eventually led us to produce the Series 700 amplifiers.

Ted Rule had been Armstrong’s electronic development engineer until I joined the company. He then focussed on developing a new FM tuner whilst I concentrated on the new amplifiers (and making some minor improvements to the 600 range). He left a while before myself. The plan at that point was that I would first finish the new amplifier designs, then switch to working on a new tuner.

However, early in 1978 I was told that development of new products was to cease at the factory, and that as a result I’d be made redundant as the development engineer. The existing company was to abandon development as it would cease to have a factory! However things weren’t quite that simple because Barrie Hope, Alex Grant, and some others wanted to go on. We’d been developing the planned 700 range wanted to see it come to the market. The aim was that if these could be made and sold and become a success, the income could be used to gradually build up a new factory from the turnover generated. However the remaining development and initial production would have to be done on a changed basis.

I left and took a new ‘day job’ working as a researcher at Queen Mary College (Now Queen Mary, University of London) on systems and devices for the ‘millimetre-wave’ region of the spectrum. This followed on from my having been an undergraduate and then a research student there before I joined Armstrong. During the next few years I did this research job during the week. It involved a range of activities from taking trips to Hawai’i to help operate heterodyne receivers, being involved in designing the optics of new telescopes, low noise amplifiers for ultra sensitive detectors, etc, etc. Cutting edge research that was great fun! But on Friday nights I’d go via tube and train from Queen Mary College down to Barrie’s then-home in East Grinstead and I’d work with him over the weekend, developing the 700 units. I’d then return to my own home back in London for Sunday night. Then off to College again on Monday morning. Barrie worked on the 700 prototypes during the week, and we discussed things via the phone or letters. Alex provided the finance to obtain the parts, etc, required. This process went on for about 4 years. During this period Barrie spent far more hours testing the amplifiers than I did, and we co-operated via using telephone calls and letters during the week. If we’d had the modern internet back then it would have made life much easier! As it was, this way of working unfortunately tended to mean development took much longer to complete.

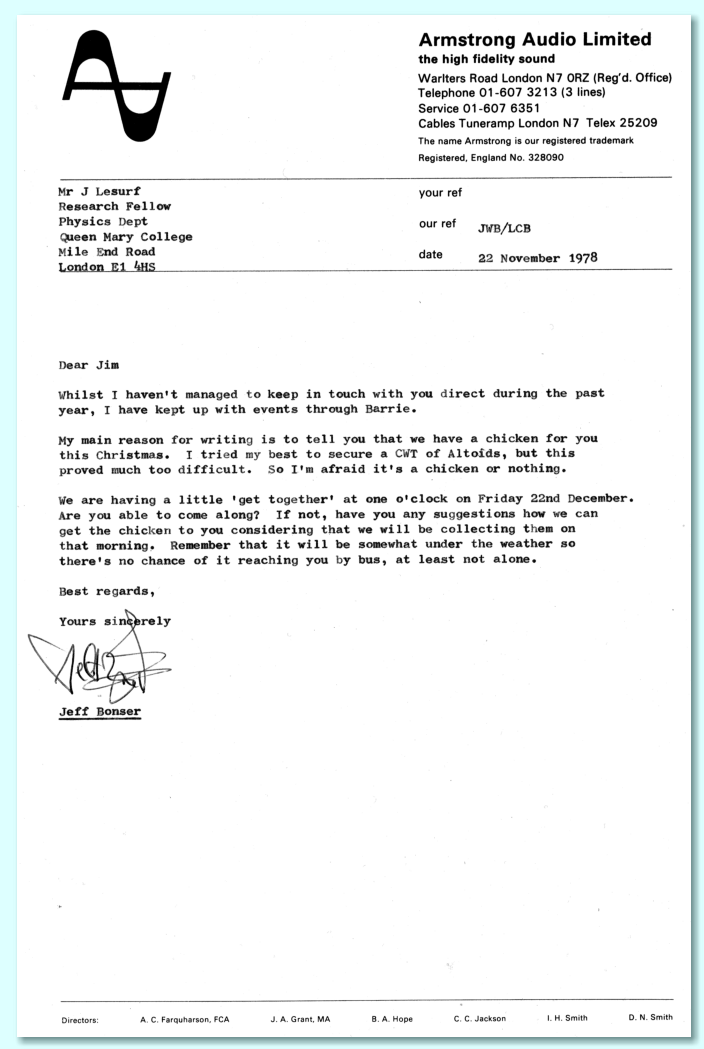

I left Warlters Rd early in 1978. An example of the ‘family’ atmosphere of the company was that I got a letter from Jeff Bonser at the end of November that year, inviting me to come and collect my traditional Xmas chicken! (I should point out that at the time I was known for always carrying a tin of ‘Altoids’ strong mints!) The 600 range sets continued to be made and sold into 1980. Following that, sales were from the remaining stock. Jeff left in December 1980 because by then sales and production had ended.

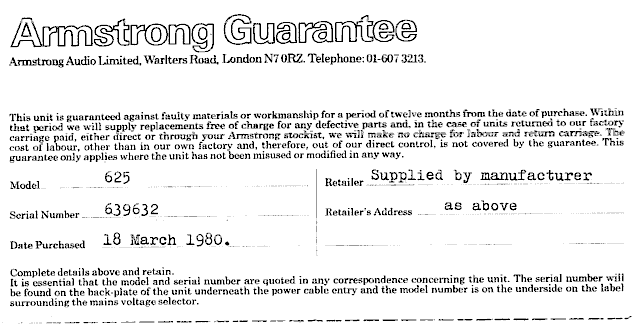

It isn't now known precisely how many Series 600 units were made in total. Twaleb Joomun of AHVS recalls that the first retail sets sold started with the serial number 600,100. Mike Solomons of London Sound recently sent me a copy of the above guarantee card. This was clearly for a set bought direct from Armstrong at, or just after, the time when actual production ended. So it is probably one of the last examples sold. You can see it was purchased directly from the factory at the time. From this it looks like around 40,000 Series 600 sets were made and sold.

After the production line was closed. Ron Sheppard, Cyril Page, Twaleb Joomun, Jeff Bonser, and Alex Grant remained at Warlters Rd, but they moved into the offices. This enabled them to continue servicing old sets, selling the remaining stock, etc. After a couple of years the Warlters Rd factory was vacated and Twaleb moved to Blackhorse Lane where AHVS (Armstrong Hi-Fi and Video Services) was established, and continues working to this day. The Warlters Rd factory was demolished during the 1980s.

In terms of the political background of the era the decision not to build a new factory chimed with the growing assumption that Britain was to become a ‘post industrial’ economy. At the time I had the feeling that what was really happening on a wide scale was that those who had the capital had decided it was easier for them to invest in things like ‘property’ (usually office space) in Britain or in manufacturing abroad than to bother with investing in British manufacturing. In effect, the outcome became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Since the capital investment for British manufacturing went elsewhere, the ability to manufacture and compete weakened for lack of support.

This showed itself in various ways during the period – both before and after I left Warlters Rd. In practice it became obvious when you compared the quality, price, and sheer range of component parts offered by British companies with Japanese ones. To illustrate this I can give a few examples...

While I’d still been working at Warlters Rd I made a number of changes to the 600 units to improve performance and reliability. One aspect of this was the potentiometers (pots) used for the front-panel controls to adjust volume, etc. The pots supplied by the initial component maker tended to be fairly rough and tended to make a noise. They also weren’t very well channel-matched. So when they were adjusted the effect on the left and right channels was slightly different. This tended to slightly ‘unbalance’ the stereo. Having tried alternatives from various suppliers I changed to using pots made by the Japanese firm who traded as ‘Alps’. These gave distinctly better performance, felt better when adjusted, and also proved more reliable.

When developing what was to become the 730 pre-amplifier I was comparing various examples of control knobs to go on the front panel controls. Since the 730/732 were intended to be what these days might be called “high end” units we wanted the best possible appearance. So the controls needed to look superb. With this in mind, again, I got some knobs from a Japanese supplier. An agent for a UK maker of control knobs, etc, visited me. He showed me examples of what they made and they all looked relatively poor. Faded uneven colour, and imprecise markings, etc. Relatively amateur appearance. I gave him the Japanese examples and said, “I’m looking for something that can match or better the appearance of this.” His response was, “You can’t make that!”

This put into words a state of mind I encountered at the time – and later – from a number of small UK companies who made mechanical components. Their assumption was that it wasn’t even possible to make better quality components than the ones they’d been making for years. The comparison made clear that a key underlaying problem for many small UK firms was a sustained lack of investment in modern machinery and improving the skills of the workers. In effect they had come to assume nothing could or would change, and that what was good enough in earlier decades was still fine. My impression was that, once again, those with the money to invest preferred to put it into property, financial speculations, or manufacturing abroad.

I’m pleased to say there were exceptions, though. For example, the 2 kVA toroidal mains transformers I chose for the 732 power amplifier came from a firm based in South Shields. Alas, I can’t now recall the name of the company. The only thing that stays in my mind is that two of the people who worked there were Mr Corner and Mr Summerbell.

A Japanese manufacturer had also been asked to provide mains transformers. The specifications were quite demanding in terms of electrical performance and low stray fields, etc, for the given size and power. The transformers also had to not mechanically hum or buzz because it is pointless to make amplifiers with a high dynamic range if you can then hear the transformers buzz! The Japanese maker designed and made (free) samples and air-freighted them to us within a week. Their quoted price - including shipping from Japan to the UK - compared with the prices of UK suppliers. Quite impressive given the sheer weight of each transformer. However the South Shields company produced transformers that were just as good, so we chose those. But the lesson here is that even for something as nominally ‘low tech’ as a large mains transformer, the Japanese were very serious competition at the time for most UK component makers.

Because of the above, to an ever increasing extent, British consumer equipment like Armstrong hi-fi gradually became filled with components made outside the UK. Cheaper, better, and more reliable as a result. Alas, the consequence was that small and medium scale manufacturers often ended up relying on large foreign firms who also sold into the same consumer markets.

In general terms people tend to assume that competitors act ruthlessly in cut-throat ways, always eager to kill off the competition. However – as with assumptions about problems all being due to ‘the unions’ – this doesn’t actually fit very well with my own experiences at Armstrong at the time. Anyone familiar with the British hi-fi makers of the period probably won’t be surprised that people at the well known and established makes like Quad, Sugden, Armstrong, etc, often were on friendly terms. Indeed, we often loaned/borrowed units from one another and exchanged ideas. There was a feeling of, “We’re all in this together, and want to make good hi-fi equipment”. What may be more surprising is that the agents of various Japanese manufacturers were also quite friendly and quite happy to loan their latest kit for examination, supply circuit diagrams, etc.

OK, to some extent, this was because they often also sold audio/RF transistors, ICs, etc. And this let you see the components you might want to buy from them later on. But it was also clear that these companies felt that the small British firms weren’t actually serious competition from their point of view. We and our sales were so much smaller than theirs in global terms that it suited them better to let us proceed, and to keep an eye on any neat ideas we produced in case they decided to copy them later on a bigger scale!

The presence of these large Japanese companies who efficiently sold into the mass market did have its effect, though. For example, when we considered the possibility of a ‘Phoenix’ version of the 600 range. In addition the technical problems it posed, it was felt that the middle ground of the UK hi-fi market was going to be dominated by the Japanese anyway. The conclusion was that in the future Armstrong and the other British hi-fi specialists would have to focus on the “high end” of the market to survive. This was why the 700 range was distinctly different to the previous hi-fi ranges which Armstrong had sold. In some ways Armstrong was actually reverting to its role decades earlier. Back then it sold high-performance radio and radiogram chassis that sought to provide a level of performance superior to the standard radio and radiograms available in local retailers. However in parallel with these changes, reviewing of hi-fi equipment in the magazines was also changing...

If you compare the reviews published in British hi-fi magazines over the decades various changes become evident. In the 1950’s and early 1960’s the reviews were mainly bench tests and sets of measurements. They were often performed by professional engineers like Stan Kelly or George Tillett who also designed equipment for various makers. For example, George Tillett designed amplifiers for Decca, and Armstrong, and also reviewed many amplifiers for Hi Fi News magazine. In some ways this is similar to the situation at the end of the 1970s and into the 1980s. Then some reviewers also acted as ‘consultants’ to hi-fi manufacturers. In each case there is a risk of problems or conflicts of interest. However there were some other differences between these eras which affected this risk.

During the 1950s and 60s it was common for a review to be sent to a manufacturer before it was published. This was to give the maker or designer a chance to comment and to flag up any possible errors or oversights in the review. As a result, the reviewer might do more tests or take into account what the maker said. And in some cases, comments from the maker were printed along with the review when it appeared in the magazine. In addition, the general approach was that reviewers, manufacturers, and designers were “all working together” because they were all keenly interested in making improved hi-fi equipment. It wasn’t simply a business, it was a common passion and interest. Everyone involved wanted to be able to hear better sound quality, and was interested in the engineering required to be able to get better results. In the event of any dispute, Hi Fi News would also publish letters from the makers, reviewer, etc, in following issues as they discussed – or argued! – back and forth. Readers could then make up their own minds having seen a fairly open, well-conducted, and rational process as a basis for deciding.

The 600 series reviews in the first half of the 1970s still show the hallmarks of this approach. For example, the October 1973 Hi Fi News review (see the 73-74 era webpage) of the 626 includes an explanation of how Gordon King measured more high-frequency distortion than specified. But he then contacted Ted Rule at Armstrong and they investigated this together. Both Gordon and Ted were radio amateurs as well as being experienced engineers with an interest in audio. So they knew one another quite well. Discussing something like this seemed quite natural and sensible to them. Their interest was to resolve and clarify any possible problems. But the key point here is that this process was carried out and described in the review that eventually appeared. (And Gordon also returned to it in a later review.) As in earlier years, the process was an open one, visible to readers and magazine editors. And it was carried out with a wish to co-operate and sort out any problems.

Alas, during the 1970s this situation was changing. From the mid 1970s onwards reviewers were increasingly failing to check any ‘odd’ results with makers or designers. And were also under pressure to get reviews done. In addition, reviewing items like amplifiers or FM tuners was developing into something more akin to ‘wine tasting’ than engineering tests! The difficulty here is that ‘subjective opinions’ can’t always be investigated or resolved, and will differ from one person and situation to another. Purely or largely ‘subjective’ reviews differences may not be resolved by discussion. Indeed, at times no-one else may have a clue what the reviewer actually means. Perhaps as a result of that reviewers gradually stopped bothering to check even their measured results with makers or designers. Leading at times to significant problems with published measured results (See, for example, the Hi Fi Choice review of the 621 on the 75-78 Era page.)

Another aspect of this was the growth during the 1970s of a ‘flat earth’ approach amongst some makers, reviewers, and retailers. During a period of a decade or more the British hi-fi market drifted into a situation where a group of reviewers and writers tended to praise or dismiss equipment largely on a ‘wine tasting’ basis. Some items made by a select group of manufacturers became regarded as the reference. In practice anything else tended to be regarded as inferior regardless of any engineering assessment, etc. The superiority of the chosen reference units was almost a mystical matter since no-one could pin it down in engineering terms!

The era has since been described as the time when there was division between the PRATs (Pace Rhythm And Timing) fans and the quaint old-fashioned “pipe and slippers” engineers and listeners. On one side, reviewers who ‘wine tasted’ and felt every amplifier sounded different to every other. On the other, engineers and developers – notably Peter Walker of QUAD – who regarded a satisfactory amplifier as “straight wire with gain” and felt that good amplifiers gave audibly indistinguishable results if used correctly within their design limits. At the time reviewing risked becoming a “golden eared club” because its assumptions implied that anyone who could not hear the claimed “differences” must be too cloth-eared to be capable of being trusted to comment. Whereas the pipe-and-slippers reaction was to see this as an example of the “emperor’s new clothes” because the claimed differences tended to evaporate when listening tests were done ‘blind’ in conditions that minimised other possible confusing factors.

Unfortunately, this was the atmosphere of the period, and it also included reviewers who would charge manufacturers money to act as a confidential ‘consultant’ for them without readers (or editors) knowing. This risked potential conflicts of interest and raised all kinds of questions like, “What would a maker do if such a consultant/reviewer made golden-eared comments which they could not translate into any engineering change?”... except perhaps make some minor tweaks and pay up for more ‘consultancy’. Given all these factors it was perhaps not a very healthy atmosphere.

Some retailers also had area-exclusive franchises to sell some PRAT-favoured makes and models favoured by the PRAT tendency. Given that these units tend to frequently be mentioned in the magazines, and usually treated as if being the gold standard, they tended from the lucky dealer’s point of view to “sell themselves”! i.e. People came into the shop and before they had listened to any equipment at all said they were interested in these specific makes and models. The shop could then easily let them listen to them for a while before they bought them. The units sold well, and typically had a 40% retail markup. So might be a license to print money at the height of the market.

One weird aspect of the period was the way what people said and believed became affected by the polarised nature of the hi-fi scene in Britain. I can illustrate that by recalling what happened when we took a production prototype of the Armstrong 700 to a well-known retailer. This was when we started looking for dealers willing to sell them...

It was clear when we started that the only speakers the dealer had ready for use with the amplifiers was the Linn Isobaraks. I should confess that I have no liking for these speakers at all. However the shop staff were keen and I knew the 700 would drive them. So I assumed that it was their shop, and it was fine if they felt the Isobaraks would help them assess the amps. However when they started playing music it soon became clear something was wrong with the sound. The shop staff started criticising the 700 amps on the “wine tasting” basis and saying it didn’t sound as good as the Naim amplifiers they usually used.

I started pointing out that there was, indeed, something clearly wrong with the sound, but it didn’t seem to me to be the amplifier. The tonal balance was, to my ears, all wrong. And the stereo image was almost non-existent. I had in fact come with Barrie Hope and Alex Grant to the shop. They didn’t really want me to challenge the shop staff in case it antagonised them, and tried to quiet me down. However I felt sure something was wrong with the speakers. Of course, since I’ve never liked the Isobaraks anyway the risk was that this was the reason. But I persisted until one of the staff reluctantly got out a sound level meter and we played some pink noise and did quick checks. It was quickly found that the two speakers did, indeed, sound quite different to one another, and measured very differently! Investigation showed that a tweeter on one of the Isobaraks was damaged, seriously reducing its treble output and almost certainly adding distortion and colourations.

Up until that point some of the shop staff had been saying “There is no such thing as a stereo image. It’s an illusion!” This was the way they dismissed my concern that the stereo image was blurred into a mush. Alas, this view that “there is no such thing as a stereo image” was sometimes asserted during that period by some‘subjective’ reviewers, etc. Their interest wasn’t in a realistic or convincing stereo image of recordings or broadcasts of live / acoustic music. Their interest tended to be in pan-potted studio constructed pop/rock music. Some of that, indeed, would not have any realistic stereo image. But it wasn’t true for all music.

One of the shop staff found a pin and and ‘popped out’ the damaged tweeter dome, like extracting a winkle from its shell! (I’ve wondered ever since if they sold the speakers later on in that state!) But despite their assuming this meant all was well, measurements and listening showed it wasn’t. So the shop staff had to grudgingly accept that what they’d been happy with had been found to be flawed. They then sadly said they didn’t have another pair of Isobaraks. Very reluctantly they brought out a pair of Quad ESL-63 speakers, saying that they didn’t think they were anything like as good as the Isobaraks. They made a point of saying how poor they thought the ESL-63s were, despite retailing them. Which left me with the clear feeling that most customers wouldn’t have been offered a chance to hear them unless they came in an insisted on doing so.

At that the point the ESL-63 had only been on sale for a short time and I’d never had a chance to hear a pair. But knowing and liking the original Quad ESL I was pleased to see them. This was vindicated when they were connected up to the 700. The results to my ears sounded truly superb. Behold! A stereo image and an uncoloured sound! The shop staff grudgingly admitted the result sounded OK, but insisted it wasn’t as good as using Isobaraks. Their focus was on a particular kind of bass sound and being able to play loud. Well, the 700 amps could output over 200 Wpcs, so did loud - indeed, could play louder than their usual amplifier. Just a shame that the shop staff had no idea what a stereo image was and couldn’t hear when one of the speakers they regarded so highly had a serious fault that changed its output so much.

The visit did shine a light into the mindset of some retailers, etc, of the period. They had become habituated to a specific sound and a surrounding set of assumptions. They ‘knew’ it was the best – to the point where they had ceased listening with a critical ear. I couldn’t claim then, or now, to have particularly acute hearing. But I could clearly hear the problem with the lack of stereo image whilst they took for granted there was no such animal. That conviction meant they were unable to actually listen and realise there was a real problem, despite their assumed “golden eared” status. A visit to another dealer exposed another facet of this.

Our experience when took the 700s to another well-known hi-fi retailer was also quite interesting. On that occasion Alex and Barrie took the amplifiers. I was called when they encountered a worrying problem. The 732 power amp included a ‘clipping detector’. The main purpose of this was to detect whenever the output voltage wasn’t a linearly amplified version of the input voltage. Thus it would detect any clipping or current limiting. It would detect even very brief (less than 10 microsecond) clipping or limiting events and light a red LED that stayed on for about a second. Hence the user could be confident that if the LED didn’t light up the amplifier wasn’t being asked for too much output. The puzzle was that at this retailer’s shop, the LED kept lighting even when no music was being played!

When I arrived we did some tests and I finally twigged the reason. The mains supply in the shop was riddled with RF spikes, etc, coming from other equipment – shop lights, etc. This wasn’t bothering the actual amplifiers in the 700 units because I’d ensured they rejected garbage on the mains. (For engineers, the amplifier stages all hung from the power rails via constant current and current mirror stages. So the amplifier’s signal path was isolated from any rubbish that might crop up on the power rails. There were also suppression caps on the rectifier bridge, etc, to reduce any garbage injection.) So when tested, none of this appeared from the audio outputs. However the clipping detector was on a separate board. The IC (TTL monostable) on that was detecting the RF spikes on the mains and lighting up. So I explained this and decided that the LED was also handy for warning users that they had spikes on their mains supply. The curio here is the way many “golden eared” reviewers and dealers worried about such RF “degrading the sound” – yet the shop had it in wholesale amounts without apparently having been noticed.

After this particular visit, as we were packing the amplifier back into the boot of Barrie’s car the dealer tried to get us to agree to him being some kind of exclusive agent for distributing/selling the units. Which was encouraging as it indicated that he felt they were likely to sell well!

The above discussions and examples relating to reviewers, dealers, etc, may help anyone reading this now to understand the context of what the general situation had become in British hi-fi by the start of the 1980s. Things had changed over the previous decade, and the changes were often not for the better! Shame, because a lot of the actual equipment being developed by various companies had improved almost as dramatically!

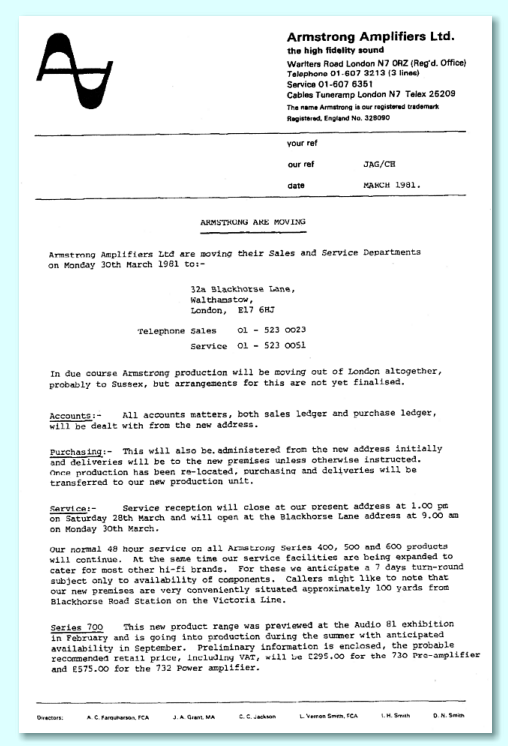

In March 1981 Alex Grant sent out a letter to Armstrong dealers and the press announcing that “Armstrong are moving”. This said that

“In due course production will be moving out of London altogether, but arrangements for this are not yet finalised”.

The plan was to set up a new production facility once the 700 units were launched. The letter also said that:

“Our normal 48 hour service on all Armstrong series 400, 500, and 600 products will continue. At the same time our service facilities are being extended to cater for other hi-fi brands. For these we anticipate a 7 day turn-around.”

The letter also mentioned the Series 700:

“This new product range was previewed at the Audio 81 exhibition in February and is going into production during the summer with anticipated availability in September. Preliminary information is enclosed, the probable recommended retail price inc. VAT will be £295 for the 730 pre-amplifier and £575 for the 732 power amplifier.”

The first mention I can find now of the Series 700 in the UK audio magazines is a brief comment on page 38 of the February 1981 issue of Hi Fi News. The issue reported that Armstrong were changing their trading name from Armstrong Audio to Armstrong Amplifiers. This was actually a sign that Barrie Hope and Alex Grant were starting a new venture using the existing brand name, etc, for the purpose of making and selling the new units. At the same time the repair and service work was handed over to another new company, Armstrong Hi-Fi and Video Servicing (AHVS). The AHVS company continues successfully to this day, and is still based at Blackhorse Lane.

A more detailed report on the Series 700 amplifiers appeared in the May 1981 issue of Hi Fi News. This was in their article on the Audio 81 show. The absence of any tone controls or switchable filters on the 700 units was a radical departure for Armstrong. The trend to omitting such controls prompted that issue’s editorial to comment on Armstrong’s decision and the clear trend to omit such controls. In fact I had it in mind to eventually design another unit with the same size, shape and styling as the 730 pre-amplifier which would provide a comprehensive and accurate set of tone controls, filters, etc. That could then be used in between the 730 and 732 or with other pre/power amplifiers. This approach would allow those who wanted tone controls and filters to have them as an optional extra. At the same time it would allow the use of high-quality precision components to ensure the results were accurate enough to avoid the problems that conventional controls could introduce. But, alas, events never got that far. Nor did events allow us to develop the intended FM tuner...

6,000 Words

Jim Lesurf

15th Dec 2015